First Viewing: Murder and Mob Mentality

by Sarah Gorr, February 22, 2017

There’s a barrier that exists around films like Fritz Lang’s M (1931), one that keeps modern audiences at bay. A long-time part of the canon, an air of mythos surrounds it that makes it feel inaccessible. Born out of German Expressionism; directed by the director of Metropolis, a silent-film spectacle often labeled one of the greatest films ever made; and settled in that area of early sound cinema that still feels incredibly far removed from the way movies are made today. Choosing to put it on can feel, as friend puts it, like eating your vegetables—one of those movies you watch because you’re supposed to if you’re a true cinephile, not because you want to.

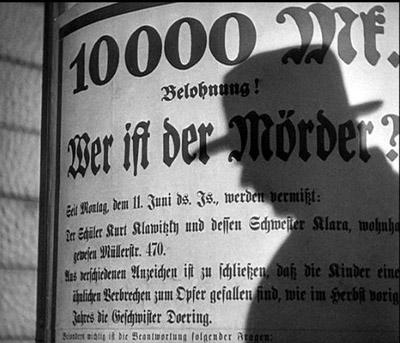

But if you can get past all of that, and if you can open yourself up to it, subtitles and all, what you’ll really find is an enjoyable, tense crime-thriller. Peter Lorre stars as Hans Beckert, a child-killer stalking the streets of Berlin. When the film begins, several children have already gone missing, and the audience catches up with him as he adds another name to his list of victims, which puts the city under a heavy blanket of fear and paranoia. We spend the majority of the film following the hunt for Hans, wondering when or if he’ll finally be caught.

After all, Hans Beckert’s guilt is never in question. For a few brief scenes in the beginning, we wonder what he looks like, what the face of this horrific evil could be, but there is no wondering who he really is, no assumption that he could be anyone. M is not a “whodunnit.” It’s not even really a whydunnit because Lang isn’t terribly concerned with why Hans does what he does (though that’s not to say his motivations aren’t addressed). Instead, we follow the Berlin police department and its shocked and fearful public as they race against each other to capture the guilty party, but those concerned citizens? They’re criminals, too.

It’s the city’s underbelly that bands together in the hopes of stopping Hans before he can claim his next victim. However, the criminals don’t band together because the police are failures. Sure, they’re angry that the police are taking so long to root this evil out, but Lang shows us in scene after scene that the police are far from inept.

The two forces keep pace with one another, the motley band of criminals using their knowledge of the streets to uncover the killer, while the police rely on classic detective work. By the time the criminals have discovered the killer’s true identity, so have the police. Watching this dynamic play out was fascinating as we currently live in a world where movements like Black Lives Matter protest the failures of the police department to hold themselves accountable for the deaths of numerous black Americans, and students protest campus policies where, more often than not, rapists return to class while their victims suffer the consequences. The failures of institutional justice are ripe in our minds.

But what’s so interesting in M is that that’s not the case for the mob’s ire. The police aren’t failing them, and by the end of the movie it seems clear that justice will be served, which leads me to wonder: what’s the question Fritz Lang is really asking? If the cops are working their hardest, if both mob and detective have pointed their fingers at the right man, the guilty man, then who has the right to deal out justice? And what does that justice look like?

These heavier questions only make M feel more interesting and relevant to a modern audience, and they only really settle in after the film has ended. In the meantime, Peter Lorre’s performance is deliciously creepy and the plot moves forward at a clip, punctuated by Lang’s artful direction. So in the end, M feels more like a treat than homework, more dessert than broccoli, and more than worthwhile, even if you don’t think of yourself as a film geek.