Scenessential: Would You Like to Know More?

by Aaron Pinkston, June 6, 2017

In order to lay out as much of the world as possible, Starship Troopers uses a series of short films and news reports designed as propaganda to catch the viewer up on the war, the alien villains, the technology, and society. And it does so remarkably well through this thinly veiled exposition. This is a technique that director Paul Verhoeven has used before in his landmark action satire Robocop and to much the same effect. There, we saw nightly news segments that described the crime epidemics alongside highly stylized and violent television advertisements that might give some insight as to how society got there. For Starship Troopers, these segments not only work as sci-fi worldbuilding but also to highlight the film’s themes of authoritarianism and extremism.

That all starts with the first image we see: a yellow logo for the “Federal Network.” This sets up the idea of media, more importantly a nationalized one. This is the very first hint Verhoeven gives that the images and messages we’ll receive shouldn’t be trusted at face value.

We then quickly transition into a military recruitment video, one that isn’t remarkably different than the ones we see regularly on television in our world—the music is loud and heroic sounding, there are big calls to action [“JOIN UP NOW!” emblazons the screen], a bandwagon approach is used with individual soldiers telling us they are doing their part, and they are incredibly diverse in terms of race and gender.

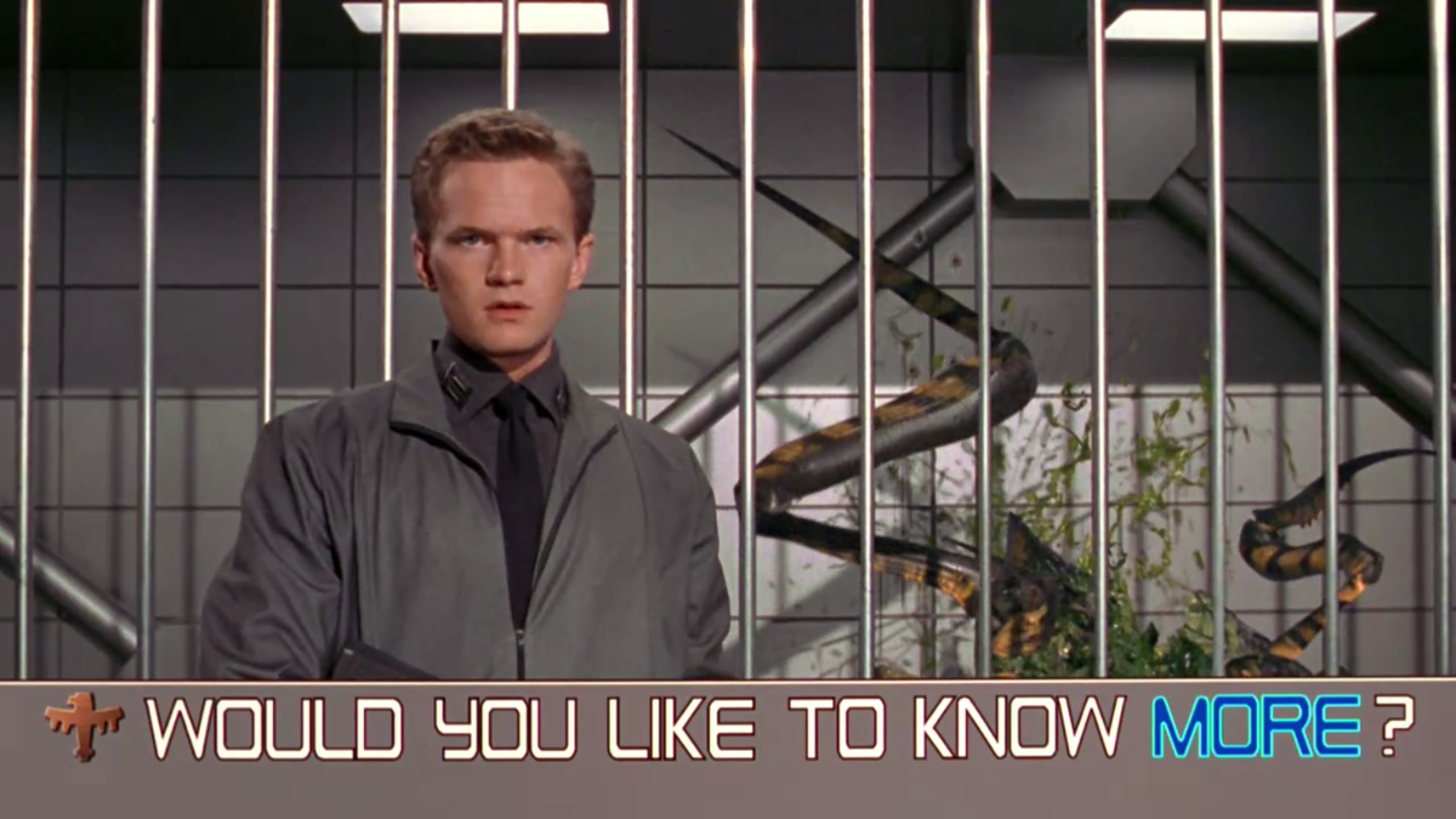

After this brief video the screen reveals itself for the first time as some sort of desktop where a user has the ability to select what information they would like to see next, with the iconic “Would you like to know more?” across the bottom of the screen. This is an interesting way to deliver this information because it seems interactive, it seems like the viewer is part of the decision making, but of course we are not. As the film uses these propaganda pieces to teach and trick the audience into understanding the world, this false sense of control is important.

We first select “Top News,” which kicks off the narrative of “the bugs.” We’re shown off the strong planetary defenses before learning more about how the bugs work and attack. Most of this information is told quickly and is a little difficult to follow—certainly by design, as we learn most of it is total bullshit.

Breaking news! We’re treated with some “live” footage of the invasion, which isn’t too pretty. This obviously is foreshadowing the climactic battle scenes of the film, though we don’t know that yet [the way the film reveals this later on is a fun and clever touch]. The scene is chaotic and dark. It is a perfect introduction, before we know anything about how the bugs really work or any of the characters we’ll be following, we can see that this is a dangerous war and the alien bugs are incredibly frightening. As in any totalitarian regime teaching its citizens about war, the less we actually know about the enemy the more scary they may seem.

The second group of vignettes comes about 20 minutes into the film, just after Rico and Ibanez have separated to their designated military appointments. We are again greeted by the yellow “Federal Network” logo before a segment called “A World That Works,” wherein soldiers mingle with children, I suppose so the kids will look up to the uninformed citizens as heroes or something. Normalizing these sorts of interactions would certainly pay dividends once it is time to meet your recruitment quotas. In true Verhoeven style, though, the interaction is completely over-the-top—ultimately with the children fighting over a giant assault rifle while the soldiers look on and laugh.

We are then treated to some more “Top News” where we learn that a murderer was captured and tried today. Who that murderer was, what sort of evidence was provided, or any details of the crime, however, aren’t shared with us. Ah, but his execution will be broadcast live at 6 pm, don’t miss it! What might be mistaken for brevity is obviously a way of controlling the social narrative. The murderer ceases to become an individual and his punishment becomes entertainment, a beloved sci-fi dystopian element. This suggests a world that could kill dissidents under these shadowy guises without question from the masses.

Are you a psychic? A creepy guy who definitely looks like a low-level yet ultra serious illusionist tells us that maybe we are! One of the most interesting minor plot elements is the idea that certain citizens may have the ability to read minds and that this skill is championed in society—we see a scene just prior to these set of vignettes where Carl is testing Rico to match playing cards.

Finally in this set we’re told about a group of Mormon extremists who set up a camp where they disregarded federal safety rules to protect themselves from arachnids—things didn’t go well for them. With incredibly gory footage of the aftermath and an arachnid in action, viciously killing a cow [for what scientific purpose, I do not know] hidden by a “censored” bar, this serves as a warning to not join an extremist group and basically do whatever the Federation tells you to.

The third segment comes near the midmark of the film, just after the destruction of Buenos Aires, Rico’s reinstatement into the military, and the final moments before the action heavy second half takes place. The tone of this group of sequences fits the tone with the cheerful, hopeful, and intriguing elements used to recruit in peacetime gone, instead cranking up the volume and the rhetoric for an angrier message.

As flames and “WAR” appear on screen we’re taken to the aftermath of Buenos Aires, where sorrow has turned to anger. “The only good bug is a dead bug!” we’re told by some random racist. We then get a message from an otherwise unknown military official who explains this is a time for action, that a human civilization must rule now and always.

Now it is time to “Know Your Foe,” where we look in on Federal scientists as they devise new ways to kill our enemies. And look at that, a familiar face! Carl [Neil Patrick Harris] instructs us that bugs are really dumb, but if you only blow off a limb, they can still be 86% effective. So, as he demonstrates, you gotta aim for the nerve stem. In the video, Carl seems like a totally different guy than the funny buddy on Buenos Aires—maybe it is just putting on airs for the cameras, but it is more likely the military complex has zapped his personality for the man who emotionlessly kills a living thing for the “good of science.”

I mentioned that the tone of this segment was heightened more in anger than comedy, but Verhoeven isn’t going to turn away from that completely, as he shows a group at home “doing their part” by squashing roaches in the street.

We transition back into our main plot with another live look-in at the soldiers preparing for battle—like Carl before, our core group of infantry are randomly chosen to express their thoughts on killin’ bugs. Our friends have fully transitioned into killing machines ready for action. The newscaster’s mention that some think a live-and-let-live policy is better than starting an all out war gets Rico particularly riled up: “Let me tell you something, I’m from Buenos Aires, and I say kill them all!” is his brief yet passionate reply.

After the deadly fight on the bug planet [the same scene that foreshadowed in the first segment], a short propaganda series updates on 100,000 dead in one hour and the resignation of the Sky Marshall. The new marshall tells us that “to defeat the bug, we must understand the bug,” which seems like a positive direction.

With rumors that there may be a “brain bug” that can think in military strategy, a talking head panel deliberates in a segment that seems incredibly familiar to modern mainstream media pundit arguments. On one side, a woman wonders that it may be possible we don’t understand everything about our enemies while her vocal opponent shrieks that he frankly finds it offensive to think there could be a bug that thinks. No real evidence or information is spread to the masses, but boy isn’t it fun to watch two blowhards yell at each other?

As the warring trudges on and the humans ultimately win the day, these segments aren’t seen over the last hour of the film, but their impact has been felt as the most illuminating and entertainment elements of Starship Troopers. They are critical to the film’s success as a satire, without them Verhoeven’s straight-faced tones may remain but the film would lack any sort of punch. They also manage to be a tolerable exposition dump, a better alternative than an opening scroll or narrator telling us what to think. Their tongue-in-cheek quality allows them to be an unreliable narrator, even as we might not know that initially. So ... Would you like to know more?